Are Bad Climate Policies Causing More Deaths Than Climate Change?

The "fact-checkers" at the New York Times need to be fact-checked.

A version of this article was originally published by the Foundation for Economic Education on 9/10/2024.

During Vivek Ramaswamy’s recent event at the Cato Institute, protestors derailed his presentation by getting on stage and chanting “climate con-man,” among other similar allegations. But it’s not just rabbles of unknown activists accusing Ramaswamy of climate falsehoods.

On the GOP presidential primary debate stage in 2023, Ramaswamy said, “The reality is more people are dying of bad climate change policies than they are of actual climate change.” The “fact-checkers” at the New York Times labeled this as “false.” But their fallacious substantiation of that conclusion reveals a concerning ignorance of the profound safety benefits of fossil fuel use, and thus the entire crux of the debate around the economics of climate change.

In their social media fact-check post, they own up to their ignorance by writing: “It’s hard to tell what Ramaswamy was referring to when he claimed that people were dying of bad climate change policies.” But then, in the corresponding article, fact-check reporter Linda Qiu mentions a key trend she found discussed on Ramaswamy’s X account. Ramaswamy had posted: “Fact: the climate disaster death rate has *declined* by 98% over the last century, even as carbon emissions have risen. The average person is 50X less likely to die of a climate-related cause than in 1920. Why? Fossil fuels. An inconvenient truth for the climate cult.”

“In campaign appearances and social media posts, Mr. Ramaswamy has also pointed to a decline in the number of disaster-related deaths in the past century, even as emissions have risen,” Qiu acknowledges.

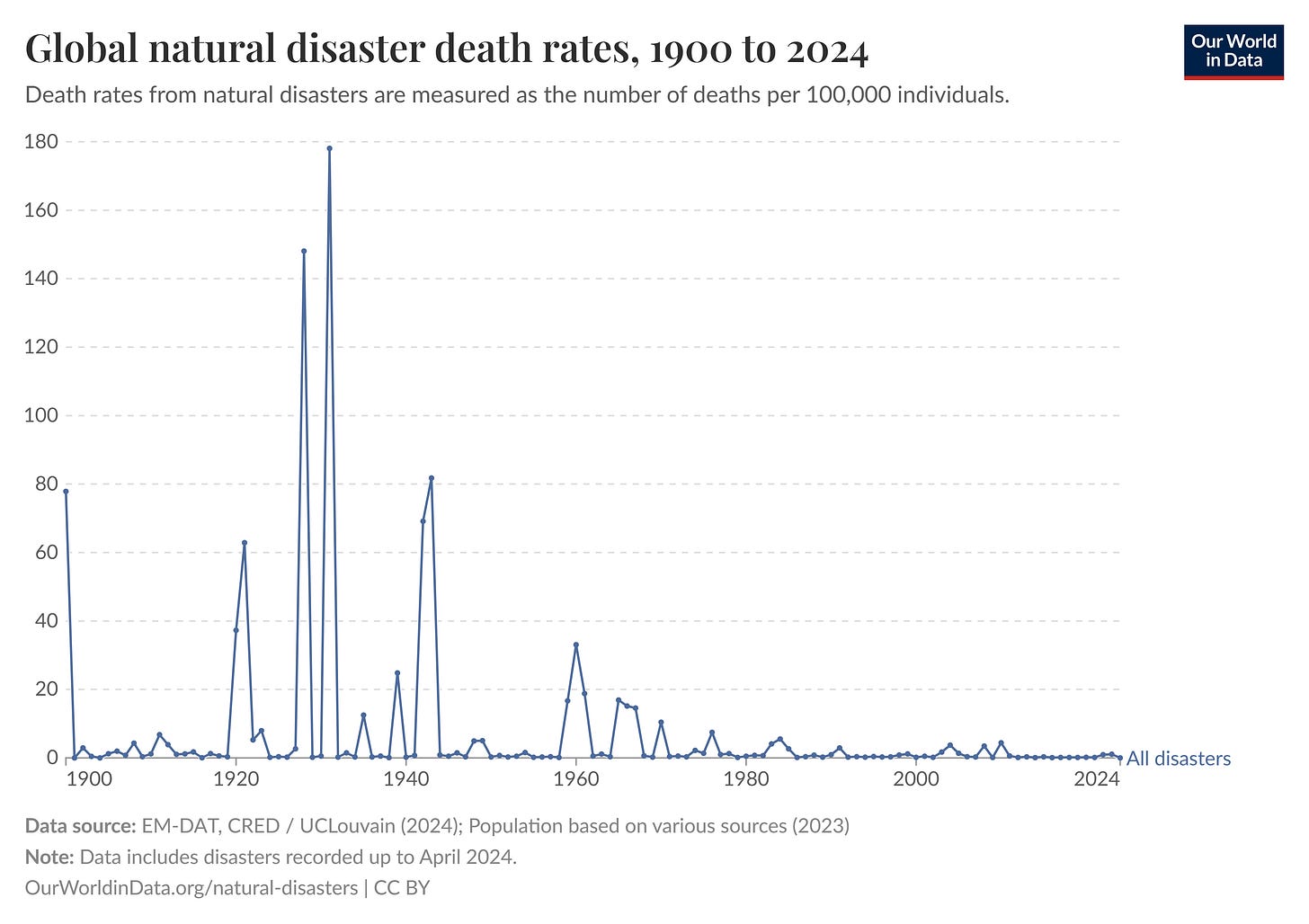

Indeed, annual natural disaster deaths have declined dramatically in both per capita and absolute terms since 1900 (the earliest year for which reliable data is available). The total death rate from climate-related disasters was 77.86 per 100,000 people in 1900, and only 0.02 in 2024. This is representative of the general trend. The statistic includes all climate-related events, such as droughts, wildfires, storms, earthquakes, and floods.

Qiu attempts to minimize the relevance of humanity’s increasing climate safety by attributing the improvement to factors such as technological advancement:

That, experts have said, is largely because of technological advances in weather forecasting and communication, mitigation tools and building codes. The May study by the World Meteorological Organization, for example, noted that 90 percent of extreme weather deaths occur in developing countries—precisely because of the gap in technological advances. Disasters are occurring at increasing frequencies, the organization has said, even as fatalities decrease.

But only if one ignores the economic benefits of fossil fuel use for technological advancement does this appear to refute Ramaswamy’s argument. The reality is that fossil fuel use, since before 1900 and into the present day, has had a massive impact on humanity’s ability to power the economy and advance technologically, especially in developing countries where people rely heavily on fossil fuels to get their basic needs met. Last year, 82 percent of global energy production was powered by fossil fuel consumption.

“The world today is unrecognizable from that of the early 19th century, before fossil fuels came into wide use,” explains Samantha Gross, director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution. “Human health and welfare have improved markedly, and the global population has increased from 1 billion in 1800 to almost 8 billion today. The fossil fuel energy system is the lifeblood of the modern economy.”

The intermittent nature of less reliable energy sources such as wind and solar mean that, even in the rare cases in which they’re price-competitive with fossil fuels, they are not a substitute but an augmentation of fossil fuel-dependent power grids, as climate reporter Shannon Osaka explains in the Washington Post:

Even in areas where a large portion of electricity is run on renewables, fossil fuels are often used to provide “firm” power that can come on at any time of the day or night. Without that power, electricity grids would see widespread blackouts. Within a few weeks, a lack of oil—still the major fuel used for trucking and shipping goods worldwide—would impede deliveries of food and other essential goods.

The New York Times fact-check article is correct to emphasize the role of technological advancements in humanity’s improving safety from climate danger, but it fails to mention that fossil fuels are a crucial resource in affordably powering those technological advancements—from powering the laboratories doing fundamental research to powering machines upon which infrastructure and disaster response depend to fueling the trucks that deliver supplies to where they’re needed most. By explaining the centrality of technological advancement to humanity’s protection against climate disaster, Qiu is inadvertently explaining the centrality of fossil fuels.

Despite the currently-irreplacable role fossil fuels play in the global economy, many countries have moved to restrict their development, citing concerns about climate change. On the campaign trail in 2019, Joe Biden said, “I want you to look at my eyes. I guarantee you. I guarantee you. We’re going to end fossil fuel.” They haven’t completely ended as promised, but Biden did stifled them enormously, from canceling the Keystone XL oil pipeline extension by revoking the necessary permit, to halting new oil and gas leasing and drilling permits in the United States in 2021 and then again in 2022, to increasing royalty rates on oil from 12.5 percent to 18.75 percent and reducing lease sales on federal lands, and taking countless other actions to reduce fossil fuel development.

A similar trend can be seen across Europe, which reduced its fossil fuel power generation by 19 percent in 2023 alone, according to the World Economic Forum.

These policies are generally in line with the goals of the United Nations, which include “net-zero targets; energy transition plans with commitments to no new coal, oil and gas; fossil fuel phase-out plans,” and other similar objectives, according to their 2023 Climate Ambition Summit.

But are these policies causing deaths?

Such widespread government-imposed limitations on fossil fuel development reduce the supply and thus increase the cost of energy throughout the global market. Because of this, many communities in developing countries and elsewhere are struggling to afford the infrastructure, supplies, expertise, and other resources they need to fortify against climate disaster. Artificially high energy costs are likely causing incalculable death and destruction at the margins of the global economy, where even minimal energy price increases can prevent homes being able to afford heating, hospitals having electricity to power their equipment, trucks having enough fuel to reach emergency sites in sufficient numbers, farms supplying their irrigation systems with running water for efficient food production, and so on.

Fossil fuel use, and indeed virtually all economically valuable material transformations of the environment, are a tradeoff between human ingenuity making the world more hospitable and environmental changes yielding unintended and sometimes dangerous consequences. Fossil fuels have extreme utility for supplying civilization with uniquely affordable and reliable energy, but they also have the negative side effect of some unwanted environmental changes.

If anything like the climate policies of Joe Biden or the UN had been widely implemented throughout the last century, humanity would be drastically less safe from climate dangers because most of the technologies now offering protection against climate disasters would never have been developed or deployed at a large scale.

Given the centrality of fossil fuel use throughout much of the modern economy—which has facilitated a level of technological development that has resulted in humans becoming orders of magnitude safer from climate change, not more endangered by it—Vivek Ramaswamy’s claim that “more people are dying of bad climate change policies than they are of actual climate change” is quite plausible.

By labeling this claim unequivocally “false” simply because they found it “hard to tell what Ramaswamy was referring to,” the New York Times “fact-checkers” have given their unsubstantiated opinion, rather than an actual fact-check, about the relative deadliness of climate change compared to climate change policies. And their opinion suggests an odd way of thinking (or rather, failing to think) about the crucial role fossil fuels have played in creating resilience against the dangers of climate change.