Environmentalist Pronatalism Versus Paul Krugman

Is reducing "population pressure" really a good way to protect environmental resources?

The original version of this article was published by the Foundation for Economic Education on 6/12/2021.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, United States population growth was momentarily at its lowest rate since the Great Depression. It has since picked back up a bit, but polling data suggests that women are still having far fewer children than they want to have.

From an environmentalist perspective, many people think this relatively stagnant population growth is a good thing. The Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman has said positive things about the environmental impact of population stagnation. He wrote in a 2021 New York Times column, “Is stagnant or declining population a big economic problem? It doesn’t have to be. In fact, in a world of limited resources and major environmental problems there’s something to be said for a reduction in population pressure.”

By expressing a rosy attitude toward the waning of humankind’s proliferation on Earth, Krugman is joining a dubious tradition that has been ascendant since the 18th century.

From Malthus to Krugman

The idea that a smaller human population is desirable on environmental grounds has been popular ever since the economist Thomas Malthus published his highly influential 1798 work, An Essay on the Principle of Population. Arguing that each plot of land could only yield so much produce, Malthus surmised that if population growth were to continue without drastic reduction, the vast majority of humanity would inevitably starve within a century of his writing.

Throughout the 19th century, Malthus’s predictions were conclusively disproved by widespread reductions in both poverty and food prices as the population continued to increase. But in the 1960s and 1970s, when the global population was roughly half what it is today, Malthusian ideas once again rose to global prominence. Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich, for example, became a celebrity by inciting an international hysteria over population growth. His 1968 book The Population Bomb became a worldwide bestseller, and he got plentiful mainstream media exposure for his ideas, including in over twenty appearances on NBC’s “Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson. Ehrlich claimed that not just food, but virtually all natural resource supplies were at the brink of collapse.

His predictions included death by starvation for hundreds of millions before the end of the 1970s (including 65 million Americans), the essential doom of India in its entirety, and even the non-existence of England by the year 2000. Perhaps his grandest forecast, made in 1970, was that “an utter breakdown of the capacity of the planet to support humanity” would arrive by 1985.

In the 21st century, population panic has shifted focus mostly to climate change. Environmentalists can now often be heard advocating smaller family sizes, or avoiding child conception altogether, in an effort to limit carbon emissions.

An article in The Guardian is titled, “Want to fight climate change? Have fewer children.” According to an NPR piece, “A recent study from Lund University in Sweden shows that the biggest way to reduce climate change is to have fewer children.” And the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published an essay titled, “Stabilize global population and tax carbon to reduce per-capita emissions,” in which it is argued that, “Tax and other economic incentives should be continuously reconsidered to make population stabilization more likely.“

Given the apocalyptic terms in which some of our most esteemed politicians and news outlets speak about the risks of climate change, these contemporary population critics can hardly be considered much less alarmist than Malthus and Ehrlich.

Hunger Versus Science

As you may have noticed, the predictions of Malthus and Ehrlich turned out to be drastically off.

Food prices have been falling rapidly, as has the poverty rate in general.

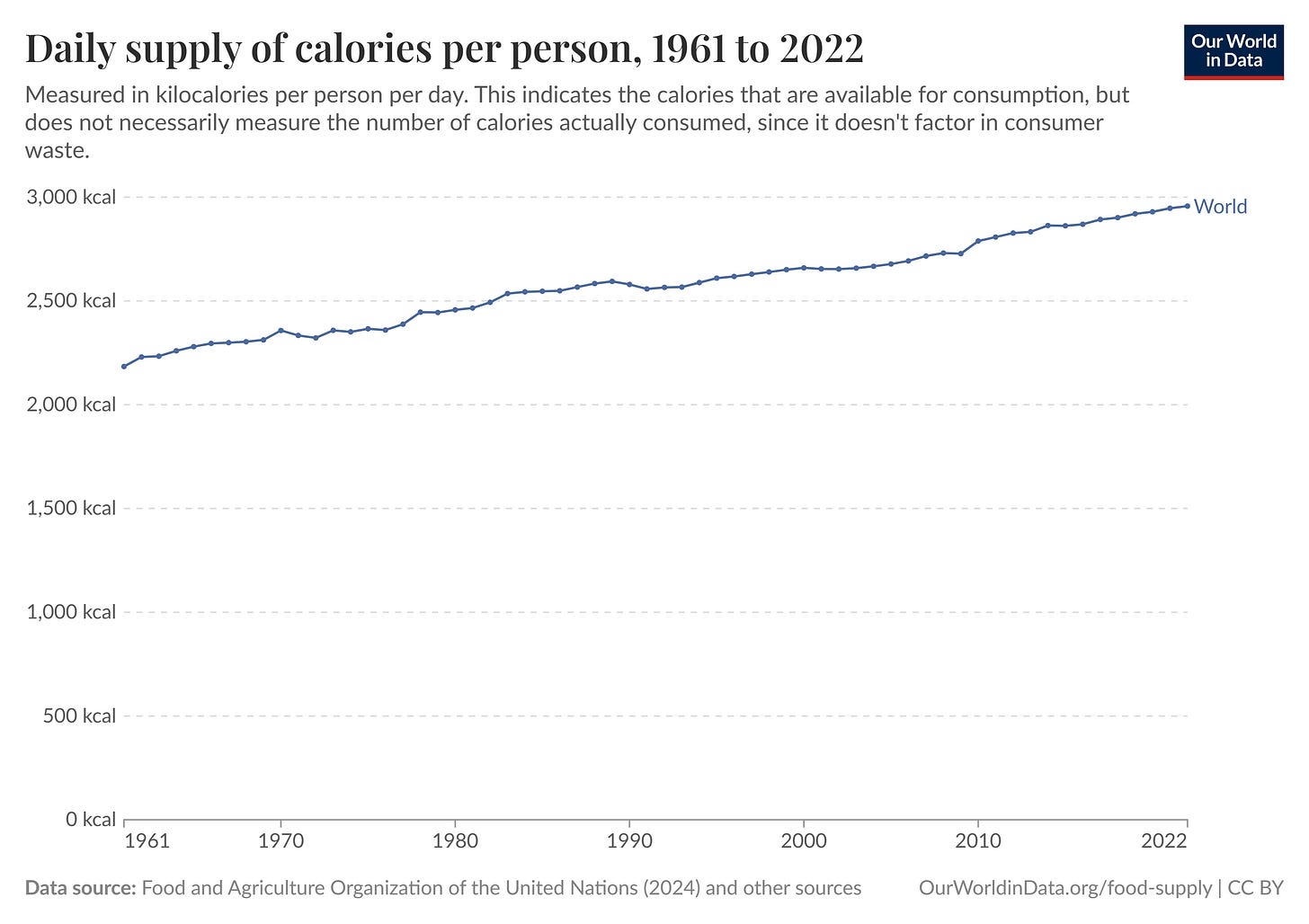

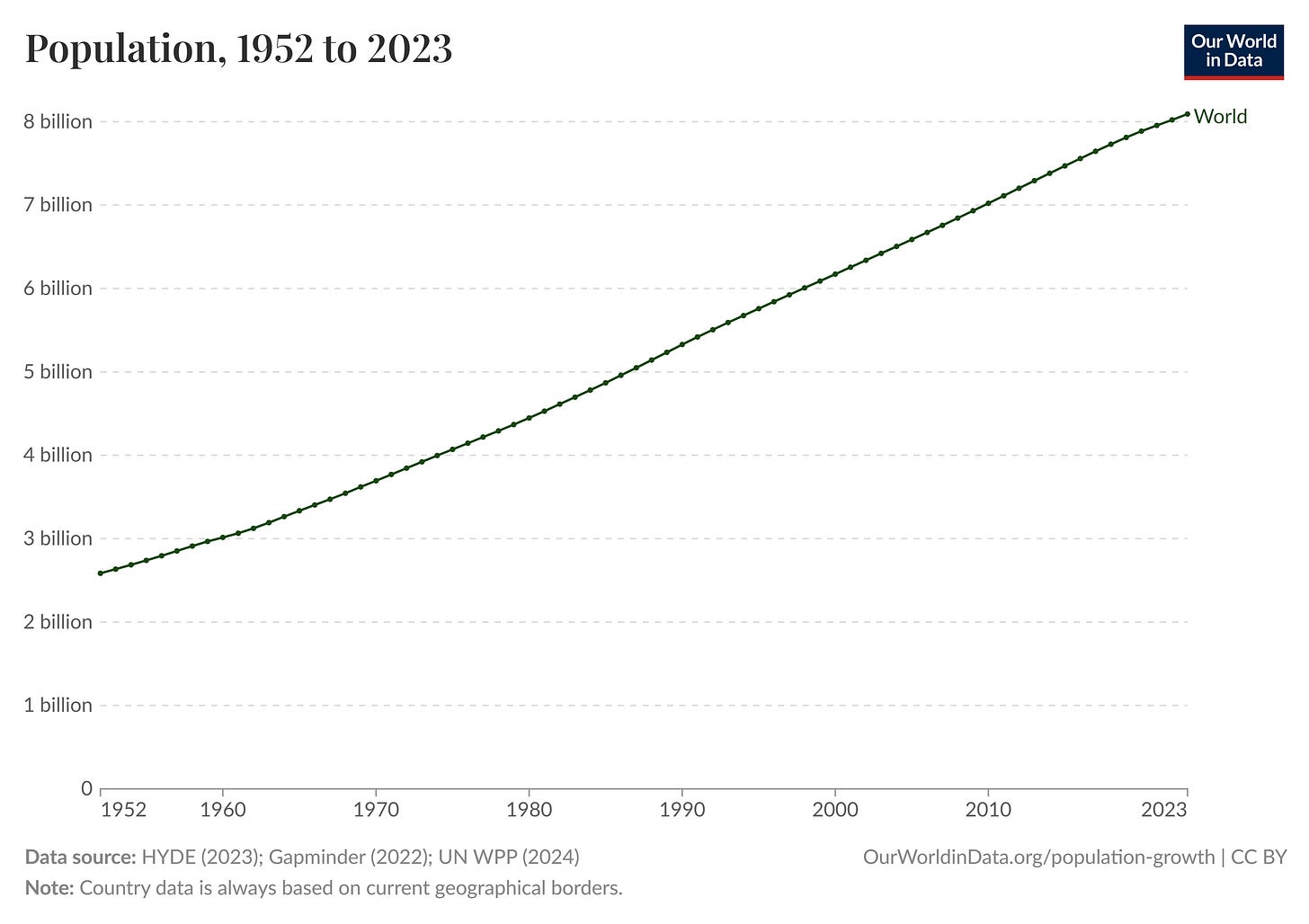

Global per capita calorie intake increased nearly every year during the period about which Ehrlich made his dire predictions. Meanwhile, the world’s human population has roughly doubled.

Reliable global undernourishment data doesn’t go back that far, but it has probably declined significantly over the same period as well.

What accounts for the radical improvements in global nutrition? The New York Times ran an article about the progress against world hunger since Ehrlich’s predictions. The author stated that, “No small measure of thanks belonged to Norman E. Borlaug, an American plant scientist whose breeding of high-yielding, disease-resistant crops led to the agricultural savior known as the Green Revolution. While shortages persisted in some regions, they were often more a function of government incompetence, corruption or civil strife than of an absolute lack of food.”

Borlaug’s innovation was part of a long trend of improvements to agricultural technology. Early that century, in 1909-1910, the Haber-Bosch process was invented, for which Haber and Bosch each earned a Nobel Prize in chemistry. Their process facilitated the creation of synthetic fertilizers, which revolutionized the capabilities of farmers worldwide and made it possible to feed a much larger population from the same amount of farmland.

Even throughout the nineteenth century, industrialization was radically improving farmland efficiency. The political economist and historian Peter Kropotkin wrote in his 1892 book The Conquest of Bread about the game-changing impact greenhouses were having on agriculture. “And yet the market-gardeners of Paris and Rouen labour three times as hard to obtain the same results as their fellow-workers in Guernscy or in England. Applying industry to agriculture these last make their climate in addition to their soil, by means of the greenhouse.”

Kropotkin noted, “Fifty years ago the greenhouse was the luxury of the rich. It was kept to grow exotic plants for pleasure. But nowadays its use begins to be generalized. A tremendous industry has grown up lately in Guernsey and Jersey, where hundreds of acres are already covered with glass — to say nothing of the countless small greenhouses kept in every little farm garden.”

To this day, agricultural breakthroughs are constantly being made that improve the ability of humankind to subsist in its environment. Just this morning, Malcolm Cochran wrote in Human Progress’s weekly news roundup that, “A biotechnology company called InnerPlant has developed soybeans that glow when stressed, allowing farmers to intervene early and avoid crop losses. Recently, their system, which pairs the fluorescent soybeans with optical sensors, detected a fungal infection weeks before it would have been visible to the naked eye.”

The Population Is the Resource

Every new human will consume resources, produce carbon emissions, and pollute their environment to some degree. But every new human also comes with a human mind, which is the source of potential solutions to these problems and many others. Each new able body also contributes precious labor to the economy, contributing to the rearrangement of the world’s atoms into more useful configurations.

The people whose future existence Malthus feared would lead to mass starvation, in some cases, turned out to be the very people who would revolutionize agriculture and virtually every other productive industry, making it easier rather than harder for future generations to be fed.

Likewise, when Krugman’s fear of “limited resources and major environmental problems” leads him to speak positively of “a reduction in population pressure,” he assumes that the destructive capacities of future people are likely to outweigh their creative capacities. But as we have seen, the history of such predictions suggests the opposite. The above-mentioned Lund University study accounts for the carbon emissions of future people, but it does not account for the creative visions of those people, nor can any study before the people exist.

Paul Ehrlich’s archnemesis, the economist Julian Simon, elucidated this fundamental flaw in Malthusian thinking. As he argued in his 1996 book The Ultimate Resource 2, “Adding more people to any community causes problems, but people are also the means to solve these problems. The main fuel to speed the world’s progress is our stock of knowledge, and the brake is our lack of imagination. The ultimate resource is people—skilled, spirited, and hopeful people—who will exert their wills and imaginations for their own benefit as well as in a spirit of faith and social concern. Inevitably they will benefit not only themselves but the poor and the rest of us as well.”

If you want to increase resource abundance and have the climate engineered to your liking, you should probably have more children. Your future descendants may be the ones to grow up and create the knowledge required to usher in yet-unseen levels of prosperity and flourishing.